FALL RIVER — After six years, Jason Burns feels he’s earned a quick breather. Then it’s back to the job of trying to save lives.

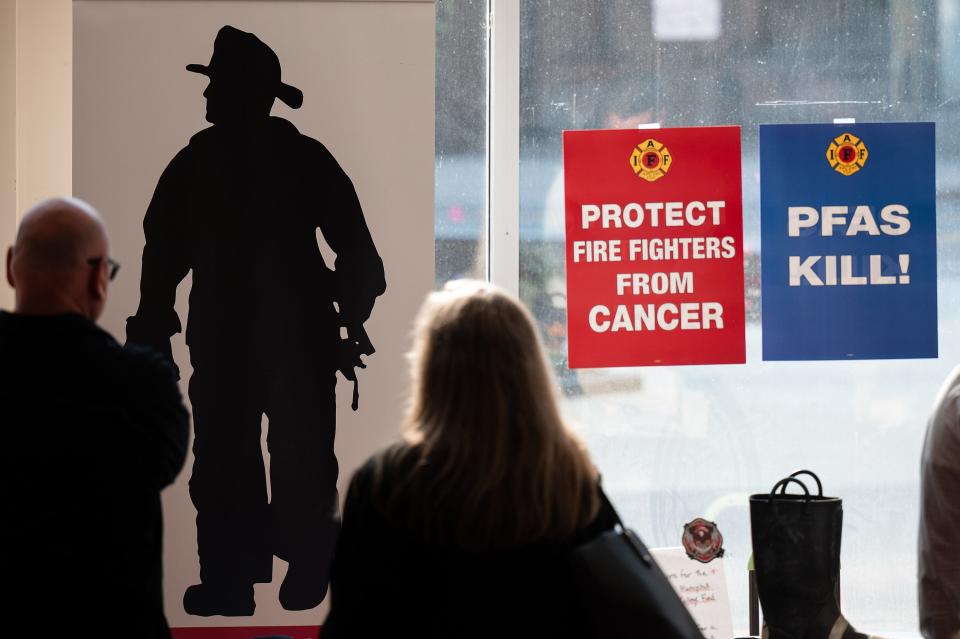

The Fall River firefighter has a longstanding side job as an activist, speaking out about the dangers of using firefighting turnout gear made with PFAS — carcinogenic “forever chemicals” used to strengthen and waterproof the material. Burns and other activists believe PFAS can shed off their gear and be absorbed through their skin, causing high rates of cancer.

In August, Massachusetts became the second state in the nation to ban the use of PFAS in turnout gear, a victory that Burns and other activists had sought for years.

Burns started his journey as a local firefighter who, when young friends and co-workers died of cancer, knew something felt wrong. He has become a notable figure who’s spoken on stages before thousands nationally. He’s been featured in the documentary short “Burned” about the subject, produced by actor Mark Ruffalo, and has become the executive director of the Last Call Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to firefighter safety.

In many ways, Burns won his fight. What does he do now?

“We’ve got to figure out the transition,” Burns said. “Let’s enjoy the moment and then regroup. Where do we go? Because we’re not done.”

‘We’re dying in that stuff’: Firefighter says toxic chemicals in his gear may cause cancer

What PFAS is and why people say it’s unsafe

The fight against PFAS in firefighting gear began with Diane Cotter, wife of retired Worcester firefighter Lt. Paul Cotter. He was diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer in 2014, had surgery and was treated, but it ended his career early.

A couple of years later, Cotter was inspired by a conversation with legal consultant and environmental activist Erin Brockovich to research whether the chemicals used to make her husband’s turnout gear could have given him cancer. She discovered that the gear — his fire-resistant, waterproof pants and coat that kept him safe — is highly saturated with PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

PFAS are a broad class of chemicals encompassing more than 9,000 known compounds, and are most useful for making products stain-resistant, grease-repellent and water-repellent. Teflon is likely the most well-known PFAS chemical, but PFAS has become commonly used in consumer products, from fast food packaging to waterproof mascara to implantable medical devices to smartphone screens.

Joining a federal lawsuit: Fall River firefighter suing chemical companies, saying PFAS in gear gave him cancer

What makes PFAS dangerous, activists like Cotter and Burns say, is that rigorous scientific studies show some of these compounds have been linked to several serious medical conditions, among them thyroid disease, high cholesterol levels, ulcerative colitis, and several different kinds of cancer — cancers of the liver, breasts, prostate, testicles, and kidneys being most common. These chemical compounds don’t break down, but can be ingested into the body where they accumulate.

Firefighters have a 9% higher rate of cancer than the general population, and a 14% higher risk of dying from it. According to the International Association of Fire Fighters, from 2002 to 2019, two out of every three firefighters who died in the line of duty died of occupational cancer.

Fall River, Nantucket team up: Can PFAS in firefighter gear cause cancer? Firefighters take part in scientific study

Burns got into the fire service, he’s said, to help save lives. When Cotter connected with him, he realized part of that mission was to tell firefighters that the gear keeping them alive could also kill them.

Since then, he’s been on the front line to stop the use of PFAS in turnout gear, becoming a known figure in the movement. He urged Fall River firefighters to join a regional study with Nantucket and Hyannis, testing the levels at which PFAS can shed off the gear and enter the bloodstream.

“Somewhere along the way I found that ability, or that voice and comfort level, to get out front and talk about these things, and have uncomfortable conversations,” Burns said. “I like doing it, and to me it fits. My job is to help people, and there’s a lot of ways to get that done.”

What Massachusetts’ law against PFAS firefighting gear does

Burns said when he and others lobbied for an end to PFAS in firefighting gear, he encountered surprisingly little resistance from legislators.

“I never encountered anyone, Republican or Democrat, who said, ‘Man I just don’t think this is a big deal.’ No one said that,” he said.

Still, getting an actual law passed took effort. Similar bills had been filed as early as 2019 and failed.

“In the end, it was a very direct conversation that I had with people,” he said. “I love the idea of your support, but I actually don’t need that. I need your vote. Bring it to a vote, but bring it to the floor, and I want your vote.”

The law dictates that companies may not sell firefighting gear anywhere in the commonwealth that contains “intentionally-added PFAS.” It is the second such law in the nation, after Connecticut, but will be enforceable earlier than Connecticut’s law, on Jan. 1, 2027. Burns said he credited state Sens. Michael Moore of Worcester and Julian Cyr of Cape Cod for their work, along with state Rep. Jim Hawkins of Attleboro.

“Ultimately it was the strongest bill,” Burns said. “Hopefully it’s a model that other states can use to protect their firefighters.”

PFAS-free undergarments: A $30K grant is buying Fall River firefighters PFAS-free gear. It may help prevent cancer.

What doesn’t Massachusetts’ PFAS law do?

The bill doesn’t immediately end the use of firefighting gear containing PFAS. Men and women are still on the job today having to use suits that contain cancer-causing chemicals, and will be for a while — Burns said in Fall River gear can be used for two cycles, or about seven to 10 years of use.

But after 2027 rolls around, cities like Fall River will have to include PFAS-free gear in their bids when buying new sets. Each set, he said, costs about $4,000.

“We know that it causes cancer. We know that it’s saturated with toxic chemicals,” Burns said. “Clearly, they have a moral obligation to get us out of it as soon as possible.”

It raises another question, yet unanswered: since PFAS chemicals are nearly impossible to break down, how do cities get rid of old gear?

“You have to incinerate it at 2,200 degrees to physically get rid of it,” Burns said. “I hope people don’t want to throw it in their landfill.“

Where the fight against PFAS in products goes from here

Beyond firefighting gear, PFAS is used in too many products to list here. The U.S. Geological Survey in 2023 estimated that 45% of the nation’s tap water contained at least one PFAS chemical. Data from the Environmental Working Group claims that 99% of all Americans have some level of PFAS contamination in their blood, including newborn babies.

Burns said he’s not as well-versed in how PFAS contamination affects other communities, but said when he was advocating for firefighter safety he met people warning of the dangers of PFAS elsewhere. He said he sees himself joining them.

“I’d be hard-pressed to ignore all the relationships I’ve built from different communities,” he said.

“I’ll tell you this: I’m not abandoning the PFAS fight because we’ve been taken care of,” Burns added, referring to firefighters. “Certainly that’s my wheelhouse and that’s what I’m always going to push, but it would be out of character to walk away from someone else’s fight at this point.”

This article originally appeared on The Herald News: Massachusetts bans PFAS in firefighter gear; what’s next for activists