“Can you imagine that confusion and hurt,” he tells them, “of not being able to fit in two places, the one where you’re born to belong and the one where you were raised? How do most people cope with that type of stress and rejection? A lot of them turn to alcohol, a lot of them turn to drugs.”

Angela Lynn McConnell had turned to drugs, at least somewhat, unbeknownst to her mother. She had also experienced another trauma that the research by the Sovereign Bodies Institute and Yurok Tribal Court found to be prevalent among missing and murdered Indigenous people: domestic or intimate partner violence.

That form of trauma is all too common in Indigenous communities. And the research indicates a possible nexus with cases of the murdered and missing: Nearly half of the Indigenous victims in Northern California had experienced it at some point in their lives, the research found. In Angela’s case, she had so feared her boyfriend at one point that she sought and obtained a restraining order against him from the Hoopa Valley Tribal Court.

It is unknown whether domestic violence was connected in any way to Angela’s death. But the nexus is just one example of the ways in which better data, and an understanding of the human stories behind that data, could help lead to fewer tragedies.

As for O’Rourke, he believes that all law enforcement officers should go into the field being more aware of the trauma that people have experienced. That training approach is called trauma-informed policing, and is increasingly being adopted by law enforcement in other communities that have been historically disenfranchised.

The chief is starting at home, with his own tribal police officers, Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike — working to remake their image as guardians of the collective good.

“Traditionally, the Yurok tribe didn’t have a warrior class or a warrior society. But we did have a village protector, that person whose role it was to make sure that the village was safe, that everyone in the village was taken care of,” he said. “They made sure that everybody had a plate, everyone had a safe place to sleep for the night, to a point where they would eat last, go to bed last, just to make sure that the village was safe. And that’s the archetype that I want to bring to this police department.”

Humboldt County Sheriff William Honsal said he’s on board with that approach. His department already deputizes Yurok and Hoopa Valley tribal police to enforce state law on and off tribal lands, which they otherwise would not be able to do. And he wants even more collaboration.

“Some sheriffs just basically ignore tribal entities and do their own thing on tribal land and don’t include input from tribal government,” he said. “And I think we’re seeing a real shift.”

Honsal also has been working closely with Yurok tribal officials.

The tribal court recently hired its own prosecutor and is now raising funds to hire an investigator who will work cold missing and murdered cases along with new ones. According to the tribe’s chief judge, that person will be working not separate from, but in collaboration with tribal, local, state and federal law enforcement.

Carpenter, Angela’s mother, said she is all for those kinds of collaborations, even across county lines. She’s convinced there are people who can break her case, but Shasta County detectives, she said, need a way in.

Tribal support

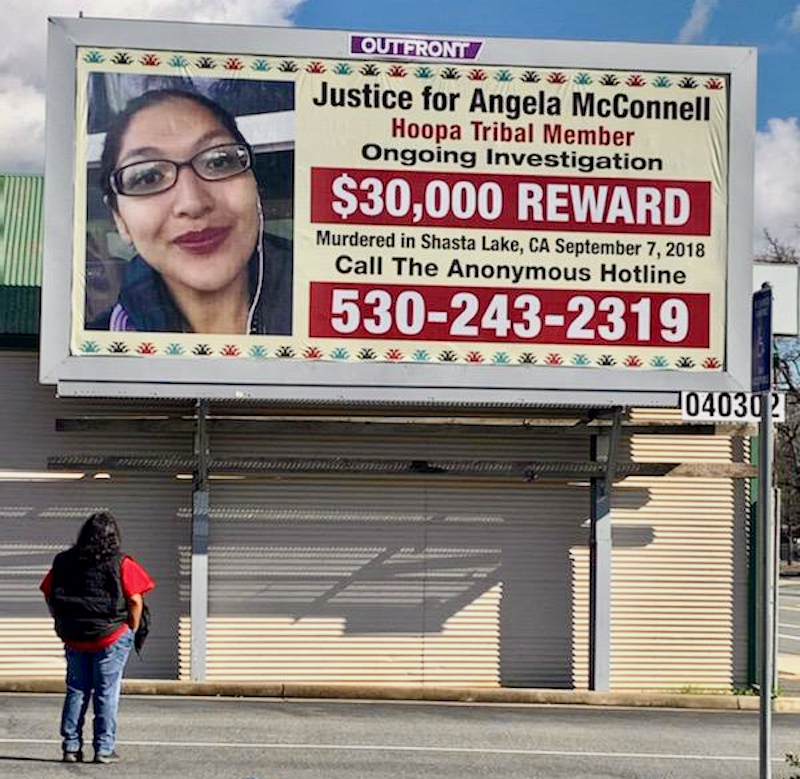

On a crisp February day in 2021, Carpenter stood in front of a massive billboard in the town of Shasta Lake that lists a $30,000 reward for information about Angela’s murder, with an anonymous hotline number. A picture on the billboard of a smiling Angela, wearing stylish eyeglasses and plum-colored lipstick, looms over Carpenter.

Filmed in a video streaming on Facebook Live, Carpenter made her plea over the roar of truck traffic, looking into the camera: “If you know anything at all about Angela, anybody that sees me on Facebook world, please contact that number.”

Carpenter also thanked the Hoopa Valley Tribe for everything it had been doing to step into the gap and help solve the case. When the one-year anniversary of Angela’s death came and went with no answers, she turned to tribal leaders, who paid for the billboard. Before that, they kicked in half the reward money. Through Danielle Vigil-Masten, the tribe’s MMIW coordinator, they also organized a march for justice on the anniversary.

In the spring of 2021, the tribe hired a private investigator, who is working not just Angela’s case, but also the unsolved cases of other murdered or missing tribal members. And those numbers, said Vigil-Masten, keep climbing.

Each disappearance or murder stirs up the trauma in all those families who have lost loved ones. It also strengthens their resolve. Ten days after another tribal member — 32-year-old Emmilee Risling — went missing, Carpenter and her family, along with Vigil-Masten and other tribal members, returned to Shasta Lake for a prayer walk for Angela.

“The mayor came. The city council came,” Vigil-Masten said. “People honked. And a lot of people came out from different tribes in the pouring-down rain.”

All of that attention seems to have helped, because not long after, Vigil-Masten said, the private investigator got an important lead in the case. Shasta County Sheriff’s Lt. Chris Edwards said he had not known about the private investigator, but he is eager to learn of any advances “so we can go follow it up with our own investigators” and, hopefully, bring the perpetrator to justice.